photo set

page of 1

page of 1

- 16

- 32

- 64

- 96

-

-

-

- .

- RM

- RF

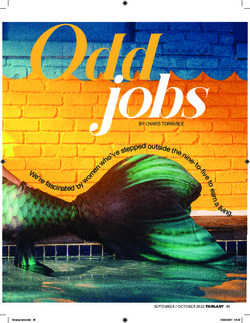

Odd Jobs

26-09-2022

2022

Human Interest

Odd jobs BY CHARIS TORRANCE We’re fascinated by women who ’ve stepped outside the nine-to-five to earn a living. MERMAID TALES Nadia Walker and Izelle Nair, the mermaid coaches AS a child, Izelle loved swimming and mermaids – she watched The Little Mermaid at least a hundred times. ‘I’m blonde, but I dye my hair red, and I’m sure it can be traced back to wanting to be Ariel growing up!’ she says. Her childhood dream has essentially come true: Izelle teaches mermaiding: how to swim just as gracefully as the majestic mythical creatures she grew up admiring. ‘It’s for fitness, it’s for fun, it’s for fantasy, it’s therapy – but most of all, mermaiding is a sport,’ Izelle says. Mermaiding was classified as a sport in Europe in 2019. Izelle first saw a mermaid coach on TV in 2019, and during 2020, when the pool next door to her yoga studio in Kyalami shut down during lockdown, she spotted an opportunity and opened her mermaid school, Merschool. Izelle and Nadia, a synchronised swimmer, offer swimming lessons and mermaid courses, as well as mermaiding parties. There are 10 basic mermaiding moves you need to master in the pool, including the backflip, glide and dolphin kick. And although these women make it look easy, it’s anything but. ‘Mermaid swimming builds your core,’ Izelle says. ‘The huge fitness advantage is that it uses every single part of your body. Because you’re swimming with a weight around your legs, your strength increases quite quickly.’ By the time you jump into the pool, you have R5 000’s worth of equipment strapped to you. Once wet, a monofin and tail can weigh 1 kg; professional mermaids use silicone tails that typically weigh 8 kg–12 kg. But don’t let that scare you off – soon enough you’ll be splashing around like nobody’s business. ‘As long as you can swim, we’ll teach you! We’ve had pregnant students, and even some in their 60s,’ Izelle says. ‘Our hope is to teach as many people as we can, and have mermaiding spread far and wide,’ she says. merschool.co.za | 071 361 8656 A CIRCUS LIFE FOR ME Nicky Slaverse and Roxanne Andrews, the aerial artists AT just 17, UK-born ice-skater Nicky Slaverse traded her skates for a life in the circus. ‘I met a trapeze artist, now my ex-husband, while I was travelling, and I just fell in love with the lifestyle. I called my mom and said, “I’m done with skating – I’m running off to join the circus.”’ The couple toured Europe for eight years before returning to South Africa in 1995 to start a circus school – with their kids in tow. When they divorced, people asked Nicky what she was planning to do next. Her reply: ‘I’ll do what I know!’ In 2011, she and her daughter, Roxanne Andrews, started The Silk Workshop, armed with very little besides years of experience and determination. ‘We didn’t even have a car then, so we walked to shows carrying our equipment, or took taxis,’ Roxanne says Nicky and Roxanne offer classes in aerial silks, the aerial hoop and the aerial hammock. They teach children from the age of 8 and adults of any age. ‘Circus training is great for fitness, but it also teaches children discipline and teamwork,’ Roxanne says. They also perform aerial and ground acts at events. Circus life definitely runs in the family. Nicky’s son Zion takes part as a skilled clown, juggler and unicyclist. ‘My siblings and I couldn’t imagine a life without the circus,’ Roxanne says. ‘I’m a circus baby – this is all I’ve known since I was born.’ Nicky did, however, make sure that Roxanne had a back-up plan. She is working towards a psychology degree, just in case. But if she’s anything like her mother, she won’t need it. ‘I will teach and perform until I can’t walk any more,’ Nicky says. Even though she’s recovering from eye surgery due to complications brought on by glaucoma, it won’t keep her off the silks for long. ‘It’s good for my soul.’ They both still feel nervous when performing, but they’re quick to add that that’s a good thing. ‘Too much nerves can be dangerous, but so can being too confident – you need the perfect in-between,’ Nicky says. One of the highest vantage points from which they’ve performed aerial silks was 25–26m, when Roxanne came down from a balcony and danced in the air over a hotel pool. Even though a performance may only be 5 minutes long, behind the scenes it takes weeks, months and years of training to be strong enough to hold yourself up for those few minutes. ‘The great thing about the aerial arts is that anyone can start – no matter your fitness level. You just need to be consistent and work at it,’ says Roxanne. ‘And have an open mind!’ Nicky adds. thesilkworkshop.com | 073 273 3538 QUEEN BEE Mokgadi Mabela, the bee farmer You could say Mokgadi, as a third-generation bee farmer, has honey running through her veins. But it wasn’t a nudge from her father, Peter, that led to her becoming a legacy bee farmer like he is (and his father’s father was before him). Although she spent her childhood eating the honey Peter would harvest from his own hives, she wasn’t all that interested in the ‘how’. As an adult, working in the corporate world, she soon realised not everyone had access to real honey. ‘I told my colleagues that what they were using in the office kitchen was not honey,’ she says. ‘Most of the honey we see on the shelves of major retailers is imported, impure and irradiated, which kills the quality and taste. I told them I would bring them the real deal.’ They were soon among the converted and she was taking orders. Word spread, and eventually Peter couldn’t keep up with the extra demand. Mokgadi decided it was time she got her own hands sticky, and opened the Native Nosi online store in 2017. Today, she keeps beehives on farms in Gauteng, Limpopo and Mpumalanga. ‘My first love is honey – but to get the honey, I need to manage the bees. Like humans, bees don’t thrive when their living space is overpopulated. We keep them on various farms so they have the resources and the space to produce the honey they need to.’ The farmers get the benefit of having the bees pollinate their crops. You’d think bee stings were her biggest concern. Not at all. ‘That’s why we have protective clothing,’ she says. Her biggest worry is humans, it turns out. ‘Vandalism is a constant problem for us.’ ‘There was a time when I thought about shutting it all down, but when I hear from people who say I’ve inspired them to do something different, it makes it worthwhile.’ nativenosi.co.za | 066 232 7780 A WALK ON THE WILD SIDE Taryn Shanna Blows, the big-cat caretaker ‘Rays, stop showing off – they’re here for me!’ Taryn teases. It’s not easy to stand out next to a tiger, especially one of Rays’ size. ‘He’s our biggest cat, our biggest eater, and definitely our biggest personality.’ (In fact, an average meal for Rays costs about R625. ‘He’s not a cheap date,’ Taryn says, laughing.) Taryn started working at Panthera Africa Big Cat Sanctuary three-and-a-half years ago. Before that, she studied musical theatre, then dropped out when she couldn’t afford it any more. Next, she worked as a server, did promotional work and worked at a call centre, before she joined the South African Navy. ‘But there were too many rules for me, so I travelled through Thailand and Bali for a year before returning to South Africa to work as a kayak guide in the Tsitsikamma.’ Eventually, she found her way to Hermanus, but working behind a desk was her worst nightmare. ‘Then I saw an ad in the local paper that Panthera Africa Big Cat Sanctuary nearby was looking for an admin assistant, and I figured if I was going to do admin, it would at least be for a big-cat sanctuary!’ Lucky for her, Panthera Africa’s owners, Cathrine Cornwall-Nyquist and Liz Cornwall-Nyquist, had other plans and offered her the role of volunteer coordinator, which quickly turned into assistant animal caretaker, and now she is the head animal caretaker. Since joining Panthera Africa, Taryn has discovered the dark side of the big-cat industry in South Africa – and why so many animals like Rays end up at the sanctuary. Cathrine and Liz were meant to rescue two tigers, siblings Arabella and Aries, from a breeding farm, but when they arrived, Aries was gone and Rays was in his place. ‘They learnt that Aries had been killed for the tiger bone trade – along with seven other male tigers. Devastated at the loss of Aries, they couldn’t leave Rays behind.’ The sanctuary is home to 28 big cats at the moment, all with similar stories. Like Rays and Arabella, a lot of them come from breeding farms. Lionesses Jade and Zakara were kept to produce cubs before coming to Panthera Africa. Other cats were rescued from zoos and from private owners who’d kept them as pets. These and many other tragic stories highlight why ‘true’ sanctuaries are so important and need more support, Taryn says. ‘To be a true sanctuary, you need to follow three guidelines: no breeding (all breeding does is create more wild animals living in captivity); no trading (we don’t trade any of our cats for profit, so when they come here it is their forever home); and no interaction. The third is the hardest for many visitors to understand, but there’s no need for human interaction – they don’t need it, we do it for ourselves.’ At times it can all feel like a losing battle. ‘There are only a handful of big-cat sanctuaries – but there are more than 300 breeding farms in South Africa.’ But Taryn remains hopeful. ‘Things are changing; there’s a growing awareness of the harm done by pseudo-sanctuaries and breeding farms.’ pantheraafrica.com | 071 182 8368 UP, UP AND AWAY Semakaleng Remofilwe Mathebula, the hot-air balloon pilot ‘I always say hot-air ballooning chose me,’ says Sema, who started her career not only very firmly on the ground, but also with a healthy fear of heights. She studied inter national relations and politics, but struggled to find a position in those fields. She ended up working as the marketing assistant for the hot air balloon company Bill Harrop’s Original Balloon Safaris. ‘My first flight was purely because you cannot sell something that you’ve never experienced,’ she says. ‘I was so nervous. I started the flight sitting down, but after 15 minutes I forgot we were free flying.’ She was hooked. That was in 2019, and even though hot air balloons have been operating commercially in South African for 38 years, there were no young black pilots. Without new blood, the industry was in trouble. To address transformation, the Balloon and Airship Federation of South Africa and the Department of Sport and Recreation got together to put three students through training, which is an expensive undertaking. One of those students was Sema. ‘We’re hoping that, through my success story, we can get more young pilots in the air and more funding for the sport,’ she says. It’s much needed: due to lack of funding and interest, this year’s South African Hot Air Balloon Championships had to be cancelled. ‘The industry has so much to offer, and all it takes is hard work, determination and curiosity to put you on the right path in aviation.’ Now that she’s qualified, Sema spends most of her days high up in the sky. Soon, she’ll have enough hours under her belt to become an instructor, with her next goal being becoming a commercial pilot. ‘For now, we’re having recreational fun, and you can hop into a basket with me by booking a flight with Air to Air Africa Balloon Safaris. ‘There’s something special about hot-air ballooning,’ she says. ‘It’s something I can’t really put into words.’ airtoairafrica.co.za instagram.com/sematheballoonist